Matthew Thorne on Tarkovsky

1. What was the first Tarkovsky film you saw, how did you react?

Solaris. When my Dad passed away, I went back through his old laser disc collection on this journey of trying to piece together more about him (and the influences that made his mind the way it was). And while I was doing that I found Solaris - a film he’d always told me to watch.

I’ve never been very good at watching ‘art films’ outside of a cinema (or in general). So I watched this expecting to fall asleep - but it just sucked me in. I think I watched it three times through one after the other. And then I started just leaving it on while I worked, like background music, instead of putting a record on, for a moment there I used to put on Solaris. And now I don’t shut up about it (just ask my friends...)

2. Why does he stand out to you?

I said this to someone on a set recently, and I think they thought I was a little crazy:I genuinely believe he might be the only true film Director… or maybe one of only a handful of people in the history of cinema that have truly made ‘film’ in whatever way film is a unique art form. He just threw away so much convention and attacked deeply into what he believed made film powerful - into this idea of it as the image of the dreaming mind. Film so often becomes business - and has been so landed in this style of Hollywood cinema that has made so much money - that the discourse of what cinema is within our own minds (and culture) has changed. Cinema to me has this unique deep, semiotic power - a living breathing Rorsach test that can be so profoundly affecting. Films just have this innate ability to live within us after watching, to be this machine that generates empathy, and operates within the dream state (in a way I think very few other works of art do).

I was talking with an incredible painter friend of mine, Felix Atkinson, recently. Whilst showing him some work, I remember he put his cigarette down at one moment, leant in, and said in this soft unassuming tone; that he really thought film (when it is art) is the highest form of art. And I agree with that. There is some unique power in the dreamscape of film - in how we watch films every night in our mind, and how film becomes - because of that connection - a kind of waking dream. But can still carry within it the subconscious power of the truly dreaming mind.

That, and I think he was one of the first filmmakers ever to truly experiment within the realm of time and its relationship to film. Works like Boyhood from Linklater don’t exist without Tarkovsky. He’s the real deal.

3. Which of Tarkovsky’s films appeals to you most? Why?

Hard to say, but I think my three favourites are Stalker, The Mirror, and Solaris. Because they’re uniquely his works, and how the push and pull the sticky medium of time - that is incredible.

4. For someone who has never heard of Tarkovsky, where could they start?

I think start with a public screening in a cinema. Tarkovsky is not a filmmaker that lends himself to being watched on your iPhone on the train to work. He’s not really a good “film director” his work is its own language - and that requires patience (and a bullheaded dedication). I reckon start with a lot of coffee, and something like Solaris or Stalker, and be prepared to push through. I have to drink lots of coffee before a Tarkovsky film!

5. How has he influenced you?

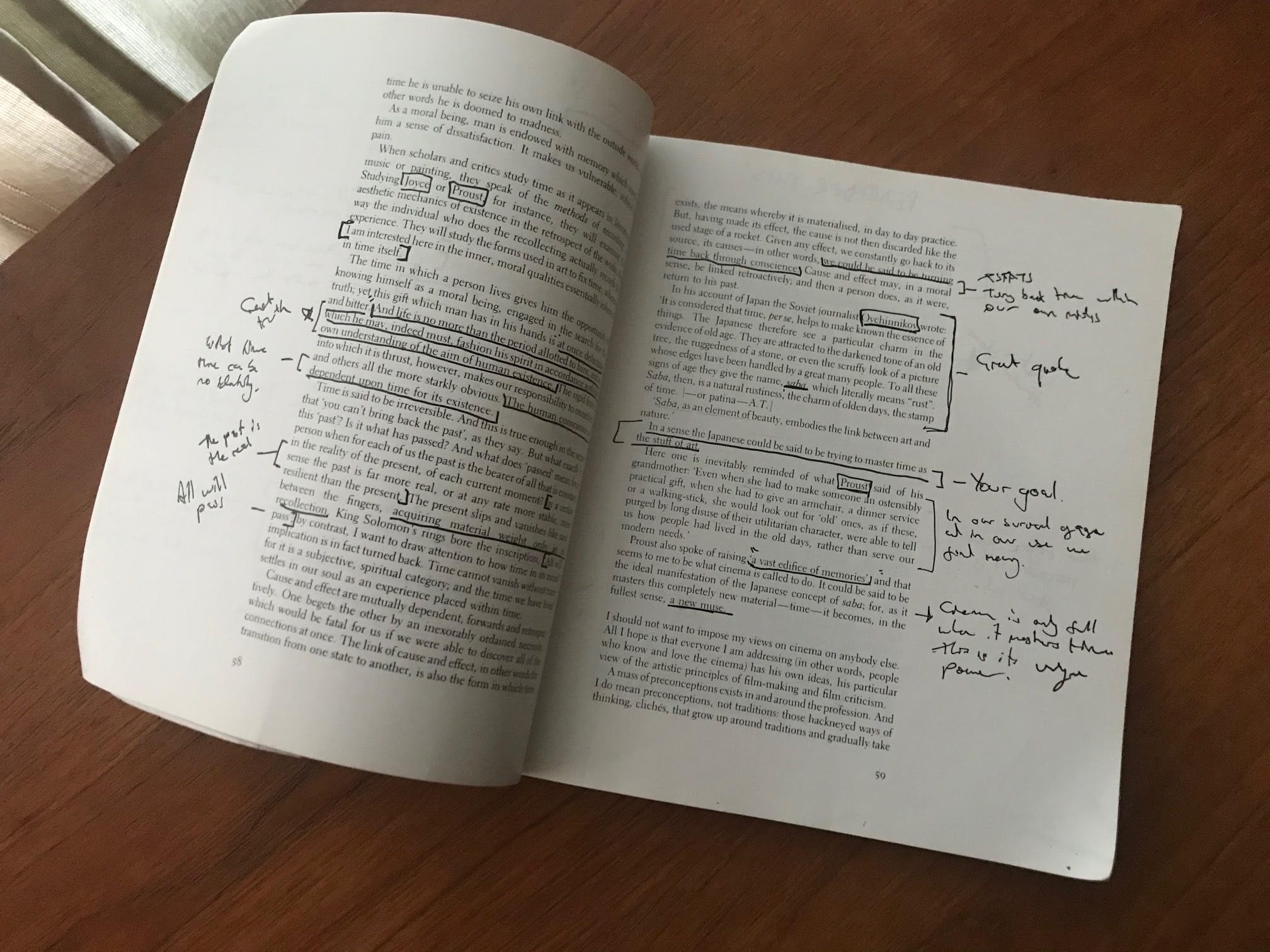

I carry his book Sculpting In Time with me almost every day of my life (and on every film and photographic series I make). It’s full of notes, and bent pages now… and I still haven’t finished it (I've been reading it for 3 years on and off, it's so dense I can only do a few pages at a time).

That book has become a big measure in an interesting way. I often ask myself ‘would Tarkovsky shoot this’ as a test of my own decision making. If the heart says no… then it has to change (or not be shot at all). He has this great theory about the importance of an image being metaphoric, but not symbolic. That symbols are the image that has firm meaning - in that they call to something that is uniquely implanted within your cultural psyche, (a burning cross, a baby crying, etc.) - and as a result cannot have any truly open and profound meaning. That profound sense comes from what he identifies as the metaphoric imagery - imagery that calls instead to something that is more interpretable - that has no firm meaning.

A famous example is in the end of one of Yasujiro Ozu’s films Late Spring where a father peels an orange alone after pushing his Daughter into marriage, and returning from their wedding. The image has no real expected cultural symbolism, but comes to possess a deep profound meaning - the image of a fathers suffering, his failures, and his loneliness. We don’t ‘know’ these things of the image in an expected, cultural knowledge - but instead can feel them innately within it (perhaps as something belonging to a deeper ability of our minds?)

I think coming to start understand that, and do my best to feel it within my own work, that was probably the influence.

6. What other films do you find special?

I think the films that feel particularly special to me, are the films that least feel like ‘films’ and most feel like the way paintings make me feel - in the same way that the Rothko room in the Tate takes your breath away with the unrelenting intent of an artist (intended or not). Those works in film tend to belong to filmmakers who sit outside the traditional commercial system of filmmaking as much as possible (Linklater, Jodorowsky, Lanthimos, Tarr, Gondry, Bresson, Buñuel, Melies, Felini, Meirelles, Kubrick, Kuleshov, Vertov, Eisenstein, Refn). People who either through bullheaded intent, luck, or fame (or all three) make films that despite often being commercial failures - or mediocre successes - still found pathways to continue making work in their unique voice and vision.

Work that truly pushes forward this idea of cinema as art - cinema as expression. For me, it feels like cinema now is caught in some strange moment akin to the era of flemish realism - great artfulness and great artists working within the style, but more made for commercial purpose than the exploration of the form or personal view.

7. Does he have a parallel in another medium?

Thats a great question. Maybe yes, many? I think he is just one of those truly brilliant artists that move the medium forward through uncompromising intent - Picasso, Monet, Basquiat, Pollock, Ray, Dylan - they’re all visions from another world and there are parallels in all mediums I think. Richard Feynman as a physicist? Everything.

8. What other directors do you admire?

All the ones mentioned here - Linklater, Jodorowsky, Lanthimos, Tarr, Gondry, Buñuel, Melies, Meirelles, Kubrick, Kuleshov, Vertov, Eisenstein, Refn - and more - Taymor, Mendes, Sorrentino, Oldman, Scott, Scorsese, Lepage, Coppola (both of them), Wenders, Hopper, Truffaut, Bresson, Fellini, Schnabel, Noé, Oppenhiemer, Malick, Kaufman, Jonze, Kurosawa, Kon, Miyazaki...

9. Have you been to Russia?

Yes - I shot a photographic series travelling across Siberia from Ulan-Ude (near the Baikal Sea) to Moscow.

It is incredible - and so like America in many ways… if I'm honest with myself I should move to Moscow and set up my life and studio there. It felt to be in such an interesting moment when I was there. Still caught between its old USSR heritage and this new potential - and there were so many incredible artists that I met in a short space of time. I remember I went to the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and it was full of people - on a Tuesday! Babushkas all wrapped up in their shawls, having a good look at some art. It was beautiful.